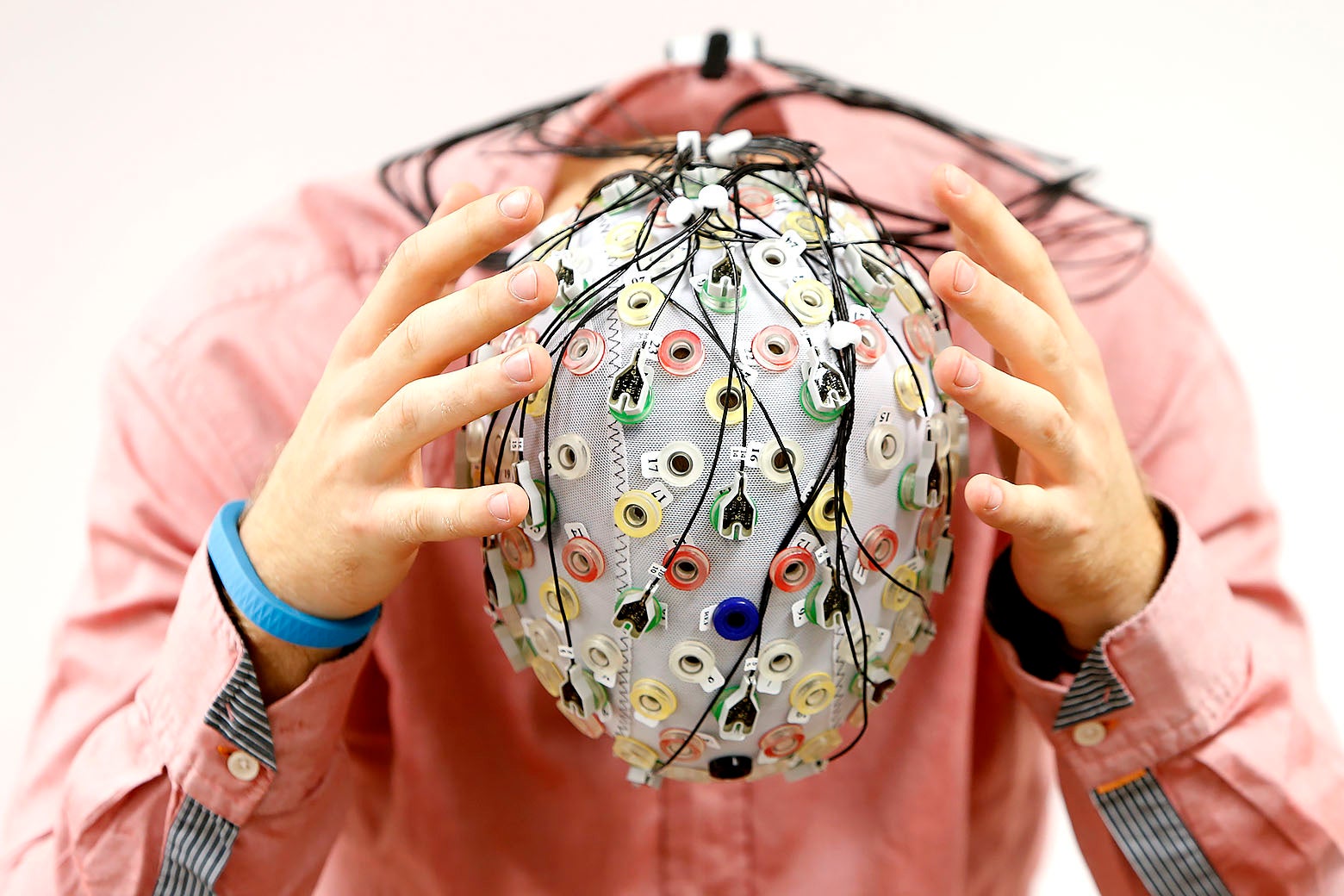

I sat in a dark room, eyes closed, with a device strapped to my head that looked like a futuristic bike helmet. For 10 minutes, while I concentrated on not accidentally opening my eyes, the prongs sticking out of this gadget and onto my scalp measured a health marker I never thought to assess: my cognitive health.

When I booked my brain wave recording (also known as electroencephalography, or EEG), I expected to pull up to an office park with medical clinic vibes, but instead my GPS led me to an ocean-view storefront decorated like a cross between a surf shop and a luxury spa, with a sign in the window promising “Mental Wellness, Reimagined.” Located in Cardiff-by-the-Sea, a wealthy coastal town north of San Diego, Wave Neuroscience promises to help your brain perform better with a noninvasive treatment that uses magnets on the brain. We’re talking mental clarity, improved focus and concentration, and even a shift in mood. As a 48-year-old whose work requires focus and creativity, I was intrigued, but also nervous. Should I mess with a brain that, while not perfect, functions reasonably well?

Getting the EEG, which costs $100, was like meditating with a device strapped to my head, but it was more relaxing than that sounds. The tech gave me periodic updates, letting me know how much time had elapsed, and afterward I was ushered into an office where I met with Alexander Ring, director of applied science at Wave Neuroscience, via Zoom. Together we reviewed my “braincare report,” a one-page analysis generated in five minutes, comparing my brain waves with Wave Neuroscience’s database of tens of thousands of EEGs.

Ring said my brain was generally performing well and that I showed cognitive flexibility and a capability to focus under pressure, but that I had a little bit more theta activity, or slow brain waves, than they normally like to see. He also pointed out a slight frequency mismatch between the back and front of my brain, which might affect my concentration and cause me to have to reread a paragraph to absorb the information. Rude, but accurate.

While the interpretation of my brain scan resonated with me, hearing my results felt a little like I was getting a horoscope or a psychic reading—I gravitated toward the parts of the analysis that felt true and ignored the rest. And even if the 10-minute EEG was accurate, the question is—what to do with this information? How could I get my brain to function at peak performance, other than removing all stress from my life and sleeping perfectly every night?

Wave Neuroscience and brain health companies around the country offer treatment in the form of transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS. This technology is approved by the FDA to treat medication-resistant depression, migraine headaches, and OCD. Clinics like Wave Neuroscience say it can also be used to improve sleep, focus, cognition, mood, and self-control. And they might be right—to a point. While science suggests TMS can improve memory and cognition in healthy adults, these are results from controlled, small-scale studies. The commercialization of this technology might be moving too quickly, especially when inducing changes in otherwise healthy brains.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation was developed by Anthony Barker in the 1980s as a noninvasive technique for stimulating the brain. It works by briefly generating a high-intensity magnetic field to stimulate nerve cells in the brain. Repetitive TMS, or rTMS—used to treat depression—delivers repetitive magnetic pulses that create small electric currents in the brain by placing an electromagnetic coil against the head, inducing an electrical current in specific nerve cells. It’s painless and safely passes through the skin and skull.

Clinics are popping up all over the United States offering TMS for wellness, promising improved brain performance. This may sound far-fetched, but the science supporting the idea that TMS improves memory and cognition has real promise, although it comes with caveats. A review in 2013 found more than 60 studies showing significant improvements in memory, motor skills, and executive processing in healthy adults following TMS treatments. A more recent study found TMS increased the subjects’ ability to recall words by 10 to 20 percent, although scientists aren’t entirely sure how long these results last. While most studies only track the immediate effects of TMS on memory, two studies from 2015 and 2019 found TMS can induce at least a two-week benefit in memory. However, some scientists worry these studies aren’t long-term or extensive enough to warrant widespread usage of magnetic brain stimulation in the general population.

The treatment offered by places like Wave Neuroscience is a variation on TMS called magnetic e-resonance therapy, or MeRT, which combines TMS technology with EEGs to deliver a treatment that’s specific to a person’s individual brain waves. Outside of the FDA-approved uses, many clinics use MeRT to treat PTSD, sleep disorders, anxiety, and head trauma.

These treatments are typically done in a clinic under a medical professional’s supervision, but Wave Neuroscience has developed a device it hopes will change that. For $6,000 you will soon be able to purchase its brand-new Sonal device, strap it to your head, and optimize your brain at home (after getting your own brain wave recording). For comparison, the far more powerful in-clinic treatments, which involve five seconds of stimulation every minute, cost about $6,500 a month. The duration of treatment depends on the individual, but most MeRT clinics recommend one month of treatment with their powerful devices, with about five, 45-minute sessions a week during that month. The less-powerful Sonal, by contrast, continuously applies magnetic stimulation for 30 minutes. Recommended treatment with the Sonal is 30 minutes a day for 30 days, followed by a brain wave reassessment to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment. For people who don’t want to purchase a Sonal device, by the end of 2022, Wave Neuroscience hopes to have Sonal available at 25 of their partner locations, where treatments will cost around $1,000 a month.

A month of daily sessions to improve my brain health and performance was intriguing. I think nothing of influencing my brain with coffee and alcohol; why not try magnets?

Not so fast, says Michael Freedberg, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin who has studied the impact of rTMS on memory at the National Institutes of Health. In an interview about using TMS to improve cognition and wellness, he told me, “There is some indirect research to back up that it could work, but we don’t have the direct clinical trials and comparative studies to say that it’s definitely going to work or even that it would do anything for the general population.”

In his research, he’s found TMS can affect the connectivity of networks in the brain—specifically, memory networks.

Freedberg said multiple studies have shown that when TMS targets the hippocampus, the connectivity strength of the brain improves.

“It’s been done several times by different researchers,” Freedberg said, “and because this area is so important for memory, increasing that connectivity strength also seems to increase someone’s memory ability. This has been done both in younger healthy adults, and older healthy adults, but it hasn’t moved yet to the clinical world.”

In these studies, subjects not only performed better on memory tests, but researchers found changes in activity and connectivity patterns when looking at the brain using functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. So maybe Wave Neuroscience is onto something—magnetic stimulation looks like it can improve memory, at least for a short period of time in a controlled research setting.

While that research is promising, Freedberg cautions that it’s still not at the level of what he would consider to be an FDA-approved treatment that could be introduced at a commercial level.

And what about the diagnostic EEG, which Wave Neuroscience uses to diagnose your brain’s strength and weaknesses, customize the MeRT treatment, and even provide insight into your personality? We track our blood pressure and cholesterol—should we also be monitoring our brain waves?

All the neuroscientists I interviewed agreed EEGs are useful for identifying traumatic brain injuries or serious deficiencies, but they aren’t meant to give a nuanced assessment of how a healthy brain is functioning, whether you slept well, or if you’re a creative and determined person. Freedberg said the method used by Wave Neuroscience matches your brain waves with a generalized ideal of what the brain should look like. What they can’t know, he said, is what optimal performance looks like for each individual brain.

“It’s very difficult to say what improper function is just from an EEG,” Freedberg said.

Sumeet Vadera—an associate professor of neurosurgery, the director of epilepsy surgery at the University of California, Irvine, and a medical adviser for Neura Health, a virtual neurology clinic—said he’s not sure a 10-minute EEG could accurately tell me that I showed cognitive flexibility and need to improve my stress management, focus, and concentration.

“The human brain is very complicated,” Vadera said, “and to get that level of information about your concentration and focus, I think that’s a very hard thing, because there’s so much variation between patients.”

Vadera acknowledges he doesn’t know the software Wave Neuroscience uses, so it’s possible this type of information can be gleaned from an EEG.

“I think that there’s certainly a truth in there,” he said.

Ring—the neuroscientist at Wave Neuroscience—told me the at-home Sonal would improve my sleep and my ability to concentrate as well as boost my memory and energy levels.

I ran these claims by Christopher Rozell, an educator and researcher at Georgia Tech who works on developing technology to enable interactions between the brain and artificial intelligence systems. Rozell was a postdoctoral scholar at the Redwood Center for Theoretical Neuroscience at the University of California, Berkeley, and researches experimental treatments for treatment-resistant depression.

Rozell told me he’s convinced by the science that shows TMS has an effect on memory and cognition.

“There have been a lot of individual studies on various degrees of cognitive enhancement. On things like working memory, executive function—speed of cognitive thought—you’ll be able to find dozens of individual papers that show you can induce performance improvements in people with TMS simulation,” Rozell said.

Rozell, then, isn’t so worried that the companies are making claims about the effectiveness of the technology—he says that it’s been shown to induce changes in brain plasticity. But that itself is concerning to him.

Throughout our life, our brain plasticity changes. Children have critical development windows when their brains are primed to absorb new information, like learning languages. As children get older, those windows close and brain plasticity decreases.

“The question is,” Rozell said, “if there was no downside to having elevated levels of plasticity, why would your body stop doing that naturally?”

We don’t know the long-term consequences of influencing our brain plasticity in adulthood, especially at a population level. Rozell said if TMS, either in clinic or at home, is creating long-term changes in the brain, then some type of plasticity is being induced.

“You’re either changing something about the brain or you’re not,” Rozell said, “and if you’re changing something about the brain, I would say we need to know way more about what the potential negative consequences of those changes are before we start letting people do this at home. Changes don’t just have positive consequences.”

I found myself thinking about the Sonal device in the weeks after my visit, whenever I had trouble remembering the details of an article I’d read a few hours earlier, or when my brain felt foggy in the afternoon for no discernible reason. I haven’t made the drive north to try to improve these issues, because while the benefits of MeRT for cognition seem remarkable, for now I’m going to stick with methods I can implement for free: exercise, limiting alcohol, going to bed early, and embracing, rather than trying to fix, the quirks and faults of my middle-aged brain.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.