Trending topics: Artificial intelligence

From brain-inspired robotics and the burgeoning metaverse to ethical content generation

and deepfakes, UCI social scientists are at the forefront of research on artificial

intelligence and its pervasiveness in our everyday lives. In the second installment

of our Trending Topics series, they offer expert insight on AI’s potential and pitfalls

in fields as diverse as healthcare, technology, climate change, digital culture and

more.

Perspectives include:

Tom Boellstorff, anthropology professor, with expertise in digital culture, disability, HIV/AIDS,

Indonesia, language, mass media, nationalism, queer studies, video games, and virtual

worlds.

Richard Futrell, language science associate professor, with expertise in linguistics, natural language processing, and Bayesian modeling.

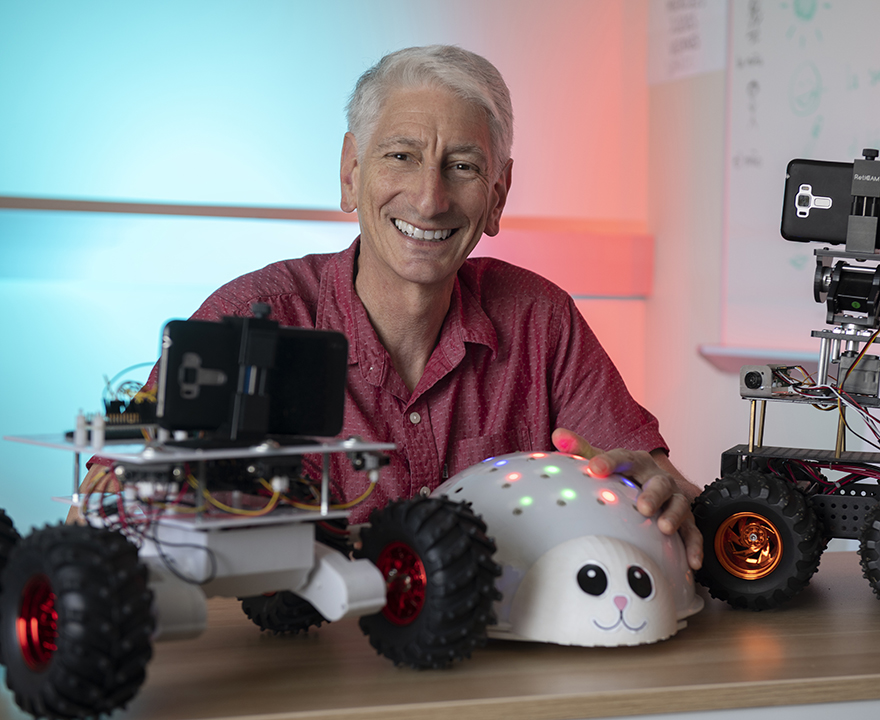

Jeff Krichmar, cognitive sciences professor, with expertise in computational neuroscience, robotics, and neural networks.

Cailin O'Connor, logic & philosophy of science professor, with expertise in philosophy of biology, behavioral sciences, and science, evolutionary game theory, and misinformation.

Megan Peters, cognitive sciences associate professor, with expertise in perception, metacognition, consciousness, computational modeling, and computational cognitive neuroscience.

Mark Steyvers, Chancellor’s Fellow and cognitive sciences professor, with expertise in higher-order cognition, learning, metacognition, hybrid human-AI systems, and computational modeling.

Main Questions:

- What role does AI play in your research and work at UCI?

- What recent advancements in AI technology do you see as having had the most significant impact on our daily lives? How is AI reshaping the way we live and work?

- This seems to be a rapidly developing and moving field. Is that the case? And as AI continues to evolve, what challenges and limitations does it present?

- What ethical considerations and principles do you think should guide the development and deployment of AI technologies?

- Do you envision AI playing a role in addressing global challenges, such as climate change, healthcare, and poverty? If so, how? What do you see as other potential societal impacts of widespread AI adoption, and how can we ensure that these impacts are positive and inclusive?

- From your perspective and area of expertise, what are the key areas of research and development that will drive the next wave of breakthroughs in AI?

- Are there emerging trends or applications of AI that you find particularly exciting or promising, and why? On the flip side, what concerns you most about its future?

- Finally, do you have any upcoming research, projects, or events that we should be on the lookout for in 2024?

Q: What role does AI play in your research and work at UCI?

Our group, the Cognitive Anteater Robotics Laboratory (CARL), creates brain-inspired neural networks to control robots. We do this for two reasons: 1) By embodying the artificial brain in a robot, we can study the robot’s behavior similar to a psychologist examining a person’s or animal’s behavior. Unlike psychologists and neuroscientists, we can record from every aspect of this artificial brain during its lifetime. 2) Despite the amazing progress in AI recently, artificial intelligence is no match for biological intelligence. Taking inspiration from biology may lead to better applications in many areas (healthcare, disaster relief, exploration, climate change, just to name a few). That being said, our field requires us to use the latest AI architectures and methods.

Our group’s research focuses on how humans evaluate how confident they feel in what they see and hear, how brain activity correlates with these abilities, and what all this might have to do with conscious awareness. We are also increasingly interested in understanding how scientists collectively think about these kinds of topics from a meta-science perspective. So we use “AI” in our group in several ways. First, we use machine learning approaches to “decode” what a person’s brain is representing when they are seeing an object, and also when they are evaluating how well they think they can see or how conscious they are of what they’re seeing. Second, we also use AI approaches to ask about how these concepts are formed in both a single person’s mind and in the collective understanding of many scientists working together. And we also ask how much of all this—whatever we find out about how the brain creates or supports decision-making and consciousness—could be useful for building smarter, more capable, and even ‘conscious’ machines.

The goal in our research group is to understand how language works: how it is that humans can hear or read language and, in real time, compute the meaning underlying that language; and how humans can start with a meaning they want to express and quickly compute the right words in the right order to express that meaning. From the evolution of the human species until about 2020, there was only one device in the universe that could understand and produce language at the level that humans do: the human brain itself. Now we have another one: large language models. So now a good research question is: is there some commonality between how the human brain processes language and how systems like ChatGPT work? It turns out there is and there isn’t. The internal structure of systems like ChatGPT isn’t much like the human brain. But at a higher level, there is a connection: for both the human brain and ChatGPT, a fundamental task is prediction of what is coming next. Your brain is always trying to anticipate what is going to happen next in any circumstance, and while you’re reading or listening to language is no exception: you are constantly guessing at the upcoming words, and this process of prediction turns out to be essential to how we understand language. ChatGPT is the same: the basic system is trained to do nothing but predict the next word in a text, like a gigantic auto-complete. So AI for us is an inspiration for understanding how language works for humans.

The research in our group focuses on human-AI collaboration with the aim to expand human decision making capabilities. Our objective is to design human-AI collaborative systems that optimize team performance and ensure that the AI communicates information in a way to optimize for human decision-making. For example, in collaboration with Dr. Padhraic Smyth, a UCI Computer Science researcher, we created a Bayesian framework for combining human and AI predictions and different types of confidence scores produced by human and AI confidence scores. The framework enabled us to investigate the factors that influence complementarity, where a hybrid combination of human and AI predictions outperforms individual human or AI predictions. Recently, we started to investigate how generative AI models such as ChatGPT (and other similar models) communicate uncertainty to humans such that they can accurately assess and communicate how likely it is that the ChatGPT predictions are correct. We showed that default explanations from ChatGPT often lead to user overestimation of both the model's confidence and its accuracy. By modifying the explanations to more accurately reflect the ChatGPT's internal confidence, we were able to shift user perception to align it more closely with the model's actual confidence levels. Our findings underscore the importance of transparent communication of confidence levels in generative AI models such as ChatGPT, particularly in high-stakes applications where understanding the reliability of AI-generated information is essential.

For the last few years, I’ve been working on a book - Intellivision: How a Videogame System Battled Atari and Almost Bankrupted Barbie® (MIT Press), which comes out in the fall. In the book, my co-author and I examine the impact of home computing on the rise of videogames, and how video games sought to make TV intelligent within the huge limits of computation. In a sense, this is an alternative history of AI. Now, I’m switching my focus to the metaverse and climate change. In June, it will be my 20th anniversary of starting research in the virtual world Second Life, and I’ve done research in several other virtual worlds as well. So it’s going to be fun for me to return fully to virtual worlds for this new project. I’m really interested in how we might make virtual worlds more climate friendly and sustainable by reducing their energy and resource use, and simultaneously how we might use them to reduce climate change and carbon impact in the physical world. I’m also interested in using VR (“virtual reality,” which I’d prefer to call “sensory immersion”) and AI to explore how climate refugees are using online spaces to create and build community as they lose their physical spaces to rising sea levels, as is the case with Tuvalu. So a few of the ways that I’m seeing AI show up in these spaces include interactions with non-player characters (NPCs) that are becoming more interactive and can remember and respond better when engaged; in-game AI that can help users build within the virtual world so that these spaces are more accessible to non-programmers; and apps and games that allow users build their own worlds.

Q: What recent advancements in AI technology do you see as having had the most significant impact on our daily lives? How is AI reshaping the way we live and work?

This is hard to answer in just a few sentences. My AI in Culture and Media class covers many of these issues. I think most alarming is the impact of social media and search engines. The AI behind the scenes for these applications are profit-driven, black boxes and persuasive. It is affecting politics, mental health, and other societal issues. We desperately need government regulation, watchdogs, and guardrails. Companies need to better explain how their algorithms work. Sadly most have no idea! On the plus side, these generative models for images and languages can have a positive impact when used properly. They can allow artists to be even more creative, help converse in non-native languages, can reduce the workload of caretakers, doctors, lawyers, hopefully professors.

There are both positives and negatives to how recent advancements in AI technology are reshaping the way we live and work. On the positive side, AI can identify patterns in highly complex, dynamic processes. For example, AI-driven climate models can be more accurate in their weather predictions than physics-based models; AI-driven drug discovery can be extremely impactful and even creative; and large language models have massively increased the speed with which we can do new scientific analyses by writing helpful code, for example. But on the negative side, these models take massive amounts of energy to train and run—and that has a serious climate impact. They also become another crutch for us to turn to when we don’t want to think for ourselves: it’s very tempting to just type a question into the chatGPT prompt and get an authoritative-sounding, clear answer. Why do any thinking for yourself, or learn anything at all, if the answers are always at your fingertips? The danger here is that we will begin to forget how to be creative, if we don’t ever have to produce anything new for ourselves. And finally, while these models are useful, many of them are locked away behind paywalls, which creates an equity issue. If you can afford to have access to these tools, you increase your competitiveness for high paying jobs, educational opportunities, and other drivers of upward socioeconomic mobility—a self-perpetuating cycle.

It’s hard to predict what impact AI will have on daily life because it is developing so quickly. Consider that in 2021, text-to-image generators couldn’t generate anything but blurry smudges, and now we can generate realistic video from a text description. Extrapolating, it’s not hard to imagine that in 5 years, anyone will be able to generate a full-length feature film based on a text description, and then enjoy that film in immersive VR. What does the world look like when this is possible? I don’t think we can say.

AI has already transformed various sectors, including transportation, healthcare, and software development, and its influence is expected to grow. Innovations such as autonomous vehicles are revolutionizing transportation, while in healthcare, AI enhances diagnostic accuracy. In the area of software engineering, tools like GitHub Copilot and ChatGPT are changing the development process. Research indicates that these AI coding assistants can reduce coding time by up to 50%, making software development more efficient. From my own experience, leveraging these AI tools has enabled me to undertake complex programming projects that were previously beyond my reach.

With regard to virtual worlds and the “metaverse” more generally, it’s safe to assume that from here on, whether we’re accessing the metaverse with VR technology, a flat screen, or even texting on a smartphone, AI is going to be there. And AI in these spaces will include the kinds of things people are doing with ChatGPT, but other things too. Consider the example I gave above of in-game AI and NPCs that you can engage with in new ways, and the ability to generate 3D environments now being open to anyone who can give it the right prompts. This will change who can access and excel in virtual worlds.

Q: This seems to be a rapidly developing and moving field. Is that the case? And as AI continues to evolve, what challenges and limitations does it present?

Yes and no. On the one hand, there has been rapid development, and for someone who has been involved with AI over several decades, it has been impressive to see how far AI has come. On the other hand, AI’s abilities have been overhyped. I roll my eyes every time I hear or read that AI is or is becoming “sentient”. True sentience or consciousness (whatever that is!) requires a living system. These are not living and do not have the same motivations as living organisms.

There are issues emerging related to AI content generation. Some of these are ethical issues surrounding what it means for a person to create something, and who gets credit when an AI helps. How do we think about student papers with significant AI input? What about AI generated art? Another set of issues relates to harmful or misleading content. In the realm of deepfakes, AI has helped people create images and videos of political figures. And there are thousands of pornographic deepfakes that use celebrity likenesses without consent. Sometimes these deepfakes actively mislead, say by making users inaccurately think that a politician said or did something. Even when these deepfakes aren’t misleading they can leave lasting impressions that harm their targets, for example by sexualizing a public figure. Since AI technology is continually developing, it can be hard for policy, law, and social norms to keep up in preventing harms from AI content.

I study consciousness (in humans) for a living, so like Jeff I also roll my eyes when I hear that AI is just about to become sentient because it seems that way. I don’t think I agree that it requires a living system, but I do agree that there are a lot of limitations in current and near-future AI systems that make it unlikely to outpace us and take over the world, at least not like Skynet “did” in the Terminator franchise. One of the biggest limitations of our current AI is that it doesn’t know what it’s wrong. It can be easily tricked by so-called “adversarial attacks” — cases where you change just a few pixels in an image, and suddenly your fancy AI model decides that an image of a panda is definitely a gecko instead. Large language models show the same kind of problem: when they don’t “know” an answer, they will just make something up, and if you call them out on it, they often say, “Oh sorry, here’s another answer I made up” if they say something true and you accuse them of falsehood, they’ll even change their answer to accommodate you! Not all AI works like this of course, but these kinds of failures indicate that none of our current AI systems really “knows” anything. They’re maybe quite good at predicting what is going to happen next, but there is no “core knowledge base” that they “believe” like a human would, and no artificial system has any core motivations. A quote I like by Daniel Dennett (personal communication to a colleague, shared publicly with permission in a paper in 2021) sums this up nicely: “How do we go from doing things for reasons to having reasons for doing things?” Humans have reasons, but so far, AI systems do not. Maybe, given the rapid pace of advancement, this will change sooner rather than later, but I think that a shift in how these models work at their core will be necessary to make these kinds of changes happen.

AI is enormously fast-developing; it’s hard to keep up even as an expert in the area. There are two reasons it’s so fast. First, obviously, there’s a lot of interest because of attention-grabbing cool results. There’s an enormous amount of manpower, energy, and excitement going into AI. There’s a huge base of people participating: it’s not so hard to teach yourself the fundamentals of AI via YouTube videos, to the point that you could implement simple systems on your own in your free time, and so lots of contributions in AI have come from young people and people without any formal credentials. Second, the progress of AI is to a large extent dependent on computing power. As computers get faster—especially graphics processing units—AI systems get better and more powerful, simply because you can take old models and make them bigger and train them on more data. One consequence of this rapid growth is that it’s hard to predict where things are going. I think we should be skeptical of any claims that there are inherent limitations to AI systems. Before around 2020, many experts in linguistics believed that no system based on statistical prediction (like ChatGPT and friends) could ever produce grammatical sentences in a human language like English, and yet this has been achieved. On the other hand, true self-driving cars remain elusive, despite the constant claim that they are only a few years away. Current systems still have limitations, such as ChatGPT’s propensity to produce good-sounding nonsense instead of true facts, but we have no idea if these limitations will be long-lasting (like self-driving cars) or merely a mirage (like generating grammatical text).

Yes, AI is a very fast moving field. Admittedly, I was a little skeptical two years ago about some of the performance claims of large-language models such as ChatGPT but now I am quite impressed by the progress of ChatGPT on various performance benchmarks. As pointed out by MP, it is true that in some cases, generative AI models such as ChatGPT do not have a good understanding of their own knowledge limits. However, we were surprised in our own research to find that in some particular cases, ChatGPT actually does have some knowledge about what it knows and doesn’t know. For instance, analysis of ChatGPT's internal representations reveals a correlation between its confidence levels and the accuracy of its responses suggesting that there is some rudimentary knowledge about its own knowledge boundaries. However, a significant challenge arises when ChatGPT articulates its confidence when providing explanations and rationale for its answers. For reasons we do not yet fully understand, ChatGPT explains itself in an overly confident manner that is not aligned with its own internal beliefs. This misalignment highlights a broader issue within AI development—achieving general metacognitive abilities and a theory of mind. These aspects involve understanding the bounds of one's knowledge and distinguishing between one's beliefs, knowledge, and goals versus those of others. Addressing these limitations is crucial for enhancing AI's reliability and trustworthiness, and I am optimistic that we will see significant advancements in these areas in the coming years.

Q: What ethical considerations and principles do you think should guide the development and deployment of AI technologies?

As I said before, we need the companies using AI in their products to be ethical when

they deploy these products. In the recent past, they have put these out too rapidly

to make a buck without thinking about the consequences. The algorithms need to be

explainable.

One issue is that AI is often used in ways that its developers might not have anticipated.

Deepfake technology has a lot of useful applications, but then it gets used primarily

to create deepfake pornography. I think a good solution is to have regulatory agencies

- similar to the EPA - that are able to respond flexibly with new policy to deal with

emerging AI-related issues.

Many large AI systems are trained on data that were not legally obtained, meaning their creators are profiting off intellectual property they stole from humans. So that’s a problem that’s going to need to be addressed, ideally with legislation. Another challenge regards sustainability and climate impact: we can’t just keep building massive server farms that hog all the electricity and contribute to global warming, all the while displacing human beings who live in increasingly inhospitable environments; a tax or other financial structure could be a way to incentivize discovery of more sustainable approaches to energy consumption by emphasizing a need for efficiency. Equitable access, as I also said before, also needs to be a driving force. We need to establish mechanisms to ensure that these tools are accessible to all, regardless of means to pay for that access. And we also need to be careful to avoid handing the keys to our whole society to systems which can sometimes behave in inscrutable, unpredictable ways and which literally reflect some of our worst failures as humans: automated facial recognition cannot be used to make decisions about arrest or incarceration/sentencing (it is trained with data that reflect human biases against people of color); AI cannot be used to decide who to hire (it is trained with data that reflect human biases in gender–and name–based discrimination); and AI certainly cannot be used to decide whether to launch a nuclear weapon or not. Placing knowledgeable experts in positions of authority to avoid these kinds of decisions should be a high priority.

If generative AI ends up playing a large role in everyone’s day-to-day lives, then the nature of the AI models is hugely important from an ethical perspective. For example, in a world where most text is produced by generative AI or with the aid of generative AI, if that generative AI only has one worldview, then it would become difficult to write anything that goes against that worldview. In a world where most media is generated by AI, if the AI model is biased toward some worldview, then that worldview would become “locked in” in almost all media in a deep way. You may already have encountered this kind of thing dealing with ChatGPT, where you ask it a question and it refuses to answer, or when it refuses to generate certain images according to its makers’ idea of what is harmful. From this perspective, an important question is who trains the AI, because the AI will end up reflecting their values. I think we should be extremely skeptical of people who claim they want to control AI in the name of “safety”: granting any group power over the contents of generative AI would be granting that group an enormous amount of power. I think the solution lies in the inherently democratic nature of statistical AI systems, which become more powerful as computation becomes cheaper. Currently only large corporations with access to large computing clusters can train a system like ChatGPT, but as computation becomes cheaper, it will be possible for more people to create models which reflect their own values. If we regulate AI prematurely, or set limits on who may develop these systems, we run the risk of creating a scenario where only large corporate entities can create powerful AI models, and I believe this is profoundly dangerous.

There are a number of approaches used to put some guardrails on AI models such as ChatGPT to ensure that these models behave ethically. One approach is based on Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). RLHF involves training AI models using feedback derived from human interactions and judgments, usually from human contractors paid by AI companies. This method allows AI systems to align their actions with human values and preferences, aiming to mitigate biases and unethical outcomes. However, this approach relies heavily on the quality and diversity of human feedback. Moreover, relying on human judgment also introduces the challenge of subjective biases and varying ethical standards across cultures.

Another recent approach by Constitutional AI takes a more principled approach, where AI systems are designed to adhere to a set of predefined ethical guidelines or “constitutional” principles. This method seeks to embed ethical considerations directly into the AI's decision-making processes, providing a foundational framework that guides AI behavior. The challenge with Constitutional AI lies in the selection and interpretation of these principles. Ethical guidelines must be carefully crafted to be both specific enough to be actionable and flexible enough to cover a wide range of scenarios. Additionally, there's the risk of these principles becoming outdated as societal norms evolve.

When the internet first got going, it was mostly a tool for universities, the government and military. There weren’t Amazons or Googles or much commerce of any type in the early days. A huge difference with the metaverse, virtual worlds and AI is that they are forming now, in the mid-2020s, and 99% are owned by big powerful corporations. It’s a very different world when for-profits are overwhelmingly running the tools that we’re all now relying on. Regulation is going to be a very important ethical consideration, but also too are the creative possibilities and constraints. There are a lot of cool things AI can do that might not be profitable, and so a corporation with a narrow vision on dollars may not explore some of these uses that could have great benefits for society. This is why I’m really interested in one of the smaller virtual worlds out there called Wolf Grid, which is a rare non-corporate owned world where some really interesting builds and developments are happening. Of course, another ethical consideration we need to always keep in mind and address is the way bias can creep into AI and algorithms. A lot of great researchers are already tracking how these forms of bias get encoded and how they can be challenged.

Q: Do you envision AI playing a role in addressing global challenges, such as climate change, healthcare, and poverty? If so, how? What do you see as other potential societal impacts of widespread AI adoption, and how can we ensure that these impacts are positive and inclusive?

Yes, in a big way. In my area, which is sometimes called Cognitive Robotics, using AI in our devices can lead to smarter robots and assistants that act more naturally. We have an aging population and a shortage of caretakers. Intelligent robots and devices can help with exploring this planet and others. Self-driving vehicles will have a big positive impact once we work out the issues. It will make our roads safer, and will increase mobility for the elderly and impaired. Another potential game changer is neuro-inspired computers. The brain is incredibly efficient. Many hardware engineers have taken note of this and are developing new brain-inspired computer architectures that need orders of magnitude less power to operate than conventional computers. This could have a big impact on climate change given that the cloud services that run large-language models, search engines, etc. require computer server farms, some of which require the equivalent amount of energy to power a small city.

Absolutely. As I mentioned in other answers, “AI” and machine learning in general can discover patterns in very complex, dynamically behaving systems that humans either may never discover, or that it would take us a very long time—and lots of expensive experiments—to work out. We already see successes in medicine, climate model predictions, and so on. If we can build AI models that we can trust, and we can work together with them as partners in scientific and technological discovery, I am extremely excited to think what we will discover together. This is one place where alignment may also play a role. Alignment refers to working to ensure that an AI system makes decisions using similar internal representations and decision policies as a human would. In other words, we want to make sure the AI makes decisions how we do, not just the same decisions that we make. Often, alignment would be pursued in cognitive reasoning, classification, or similar kinds of domains where we’re trying to build AI that can help solve problems. This could help make AI a useful partner in science or technological development, because it would “think” more like a human partner. But we could also use alignment approaches to ensure that the value an AI system places on e.g. equitable treatment or access to resources is as high as (or higher than) the value assigned by humans. Establishing guidelines for AI development that targets ethical or moral alignment with values shared across cultures, and those which preserve the habitability of our planet, may help steer us in a positive direction.

There are so many amazing things AI can do, and as so often happens with newer technologies, the biggest things are probably things we can’t quite imagine yet. AI will certainly have usefulness in addressing climate change in many ways. It can respond to challenges in healthcare; there are already AI tools being developed that can listening to and transcribe patient visits, thus cutting down on the time doctors and nurses spend on their laptops. Even in an area like real estate, we see AI already used as a time-saving way to autogenerate home descriptions, seamlessly translate between multiple languages, and more. It's like the internet in the early 1990s: we really are just on the ground level of where AI will go from here.

Q: From your perspective and area of expertise, what are the key areas of research and development that will drive the next wave of breakthroughs in AI?

I think biologically inspired AI. It is already happening. Current AI is reaching a plateau and people are looking to biology to make their systems learn faster, learn more, and adapt to change.

We desperately need “AI” that is flexible and adaptable. “Generalizability” is the term that often gets used here—systems need to be able to behave appropriately in situations that are not within their training sets. A self-driving car that learned to drive using millions of hours of training data may mostly behave okay, but then when it encounters something outside that training set, it may behave erratically in ways that a human never would (and which place human life at risk). An AI system that learned to classify images of objects needs to be able to tell when it sees a new object that absolutely does not fit into any category it has learned. These kinds of capabilities are rapidly being developed, but we still have a long way to go. Here is where we can gain great benefit from studying how humans behave adaptively and flexibly under uncertain and unfamiliar conditions. Humans are the proof of concept: we’re pretty good at staying alive, evolutionarily speaking, so if we can learn how we behave in these generally intelligent ways, we may be able to create AI that is more generally intelligent.

I think big breakthroughs in AI are going to come through big breakthroughs in hardware: especially chips that can run the computations needed for AI in a way that is much more energy-efficient than the existing hardware. We know that it’s possible: the human brain uses much, much less energy than any graphics processing unit.

I think that AI systems can be vastly improved by learning from direct interactions with people. Currently, the majority of the data used to train AI systems are based on passive observations of human language. I believe learning can be accelerated if the AI is more “in the loop” and actively involved in our conversations. This will force the AI to learn how to keep track of the conversation and develop more nuanced and personalized representation of the people engaged in the conversation.

There’s an emergent area exploring how AI is actually used. A lot of research is on what it does, but we also need to track how it’s actually used. When we look at the history of technology, we see over and over again that a technology designed for X purpose gets used for that purpose, but then gets used for Y and Z as well—new uses never imagined at the outset. After all, the internet wasn’t originally intended for Netflix, and yet, here we are! So it will be interesting to see the unexpected ways AI will be used.

Q: Are there emerging trends or applications of AI that you find particularly exciting or promising, and why? On the flip side, what concerns you most about its future?

I find it all very exciting. I think if we are thoughtful about AI development, there is going to be far more good things than bad things coming out in the near future. Hopefully in the areas I mentioned, and probably in areas I never imagined. Despite the hype, this particular AI wave seems different than past ones.

The pace of AI development is truly, gobsmackingly astonishing. With jaw-dropping announcements coming from all angles at rapid pace, it’s beginning to look like the dawn of some of our favorite science fiction narratives: powerful systems that can help solve problems humans could never hope to understand, or which can facilitate discoveries that can make all our lives better. But it’s scary, too. I’m not scared that AI is going to “go bad” and turn us all into batteries like in The Matrix or anything, but I am worried that its continued advance will both exacerbate the societal and environmental problems we have now while also slowly chipping away at our creativity, critical thinking skills, and independence. It’s already bad enough for us all when telecommunications systems, transportation, or other utility infrastructure goes down for a few hours. Should we become even more completely dependent on AI for everything—education, healthcare, communications, etc.—if it fails to behave as we expect, we might not know how to do much for ourselves anymore.

My focus and specialization is on the metaverse. In terms of the hype cycle, the metaverse was big and then it became less of a headline when the conversation switched to AI. But the metaverse isn’t going away. People doing things in online spaces isn’t going away. In the wake of COVID, there’s lots of interesting stuff - lots of lessons learned after being thrown into the deep end and making things work. And of course, some things we did during COVID didn’t work so well. But we shouldn’t take that as a measure of what’s possible. Virtual worlds have incredible potential for creative responses to climate change. Consider how often we now forego driving to a meeting and instead hop on Zoom. That’s reducing cars on the road and our overall carbon footprint. What do virtual worlds make possible that Zoom does not? When we think about climate change, there’s often a sense of hopelessness, but if these online worlds and AI tools can help reduce measures by even 1%, that’s huge. The danger is that we don’t want these tools moving us in the other direction. And we also need to keep in mind that key concerns about inequality and access aren’t going away with rise of AI and the metaverse. They’ll just take new forms, but also there will be new ways to work toward inclusion and access: there is not a sustainable, effective path to our climate change response without that.

Q: Finally, do you have any upcoming research, projects, or events that we should be on the lookout for in 2024?

Sure. We have collaborative research with Liz Chrastil in UCI’s Biological Sciences and Doug Nitz in UCSD’s Cognitive Science on how people, animals and robots find their way around. You may see some of our robots roaming around Aldrich Park. We are working in the area of neuro-inspired computation. Just recently our team was granted a Beall Applied Innovation Proof-Of-Product award and invited to participate in the National Science Foundation’s I-Corps program to investigate the commercial viability of our software framework. Lastly, I have been working with an enthusiastic interdisciplinary group of undergraduates who are creating a really cool intelligent robot. We are in stealth mode currently, but expect to hear more from them this Spring!

I’ve participated in several large consortium projects on how we might test for consciousness in AI, and how we might build components of what we think brains are doing to create consciousness into artificial systems. Look out for some of these papers in the near future! I also talked with the Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory on March 7 for their “Evenings to Remember” series, on consciousness in AI. I’m also contributing to a new summer school workshop course that Neuromatch is launching this summer, on ‘neuroAI’, which will discuss promises and limitations of neuroscience-inspired AI systems and using AI for neuroscientific discoveries; the workshop components I’ve volunteered to build are all about consciousness and ethics in AI, neuroscience, and their intersection.

In a new project with the Honda Research Institute, I am broadening the scope of my research on human-AI collaboration to include aspects of well-being as well as efficiency and accuracy. Autonomous agents will play a large role in mobility in future societies through autonomous vehicles and robots, and it will become increasingly important to cooperatively adapt the behavior of these autonomous agents to promote prosocial behavior that can affect overall wellbeing. The project's goal is to investigate the tradeoffs between prosocial behavior and autonomous agent efficiency. Our long-term goal is to understand how prosocial behavior of autonomous agents can improve prosocial behavior among humans and create better societies.

Be on the lookout for my book, Intellivision: How a Videogame System Battled Atari and Almost Bankrupted Barbie®, around October. And definitely more to come from me on the metaverse and climate change!

connect with us